Photography and Snowflakes

It is generally believed that no snowflake is the same because of one man and his obsession with looking at snow crystals: Wilson Bentley. Over the course of his life, Bentley photographed over 5000 snowflakes which were collected from around his home in Vermont over his lifetime (1865-1931). This impressive collection sparked curiosity among the scientific community into how snowflakes form and cemented Bentley's place as the most dedicated observer of snow in history. I came across Bentley's work whilst reading a book about snow, and his photographs and story have captivated me.

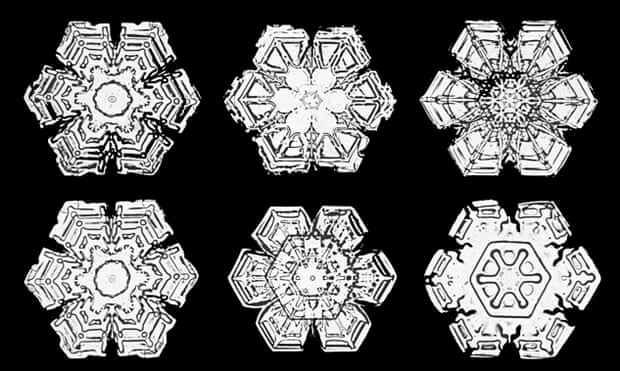

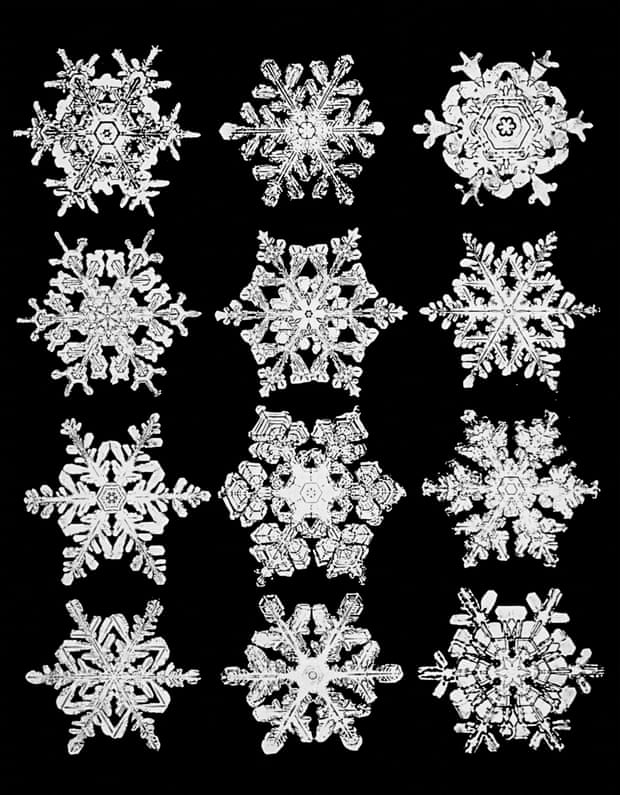

A snowflake will have one of a specific number of structures - such as dinner plates, branch networks, columns and 'flower' patterns - but with different detailing that makes it unique to any other. Up close, these internal symmetries and dendrites appear intricate and beautiful and is what captured the attention of Wilson Bentley as a fifteen year old boy when he first put a snowflake under a microscope.

‘Under the microscope, I found that snowflakes were miracles of beauty and it seemed a shame that this beauty should not be seen and appreciated by others’. A series of plate snowflakes captured by Wilson Bentley. Source: The Guardian

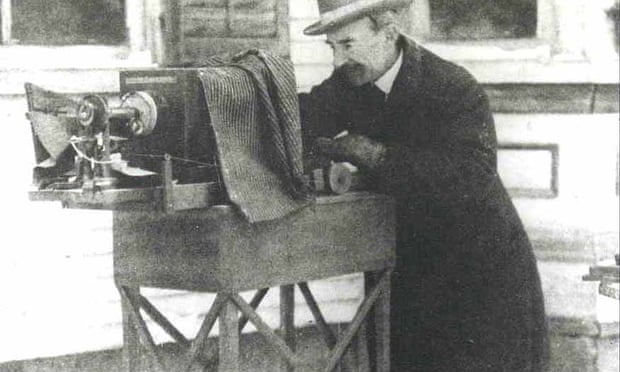

Wilson Bentley lived all of his life in Mill Brook Valley, a small place in Vermont (New Hampshire, USA) which lies adjacent to the Green Mountains of Vermont and commonly receives high snowfall in the year. On receiving a microscope as a birthday present from his parents, Bentley became obsessed with looking at snow crystals gathered from around the town. A couple of years later he attached a bellows camera to his microscope and began photographing snow crystals. Microscope photography is now referred to as photomicrography, and Bentley was the first person in the world to perfect this technique.

Bentley's set-up consisted of the bellows camera on top of the microscope, with a series of attached pulleys and strings that controlled the focal length and focus of the camera. He would take a three-inch plate and create the luminous white shape of a snowflake on a field of black by scratching off the black emulsion from the photograph negative. Over a period of 50 years, he photographed more than 5000 snow crystals and eventually published a selection of these in 'Snow Crystals' in 1931 which propelled him to fame and attention from the scientific community.

Wilson Bentley in action with his set-up for photographing snowflakes (source: The Guardian)

Even when he was beginning to be acknowledged for his work in the 1920s, many people in the town thought he was mad for isolating himself in his garden shed obsessively studying snowflakes, including his father and his brother. At this point, he had been published in news outlets such as the New York Tribune and the Boston Herald, and was even featured in a short film called 'Mysteries of the Snow'. He didn't massively profit from this success, instead being content in doing the thing he loved. Shortly after his book 'Snow Crystals' was released, he died of pneumonia after insisting on walking back to his home through a blizzard.

Future studies showed that Bentley had only scratched the surface on snow crystal structures, partly because he exclusively studied snowflakes from Vermont. After his death, the scientific community became interested in exploring snow crystal structures, growing snow crystals in laboratory condition. This was largely led by Japanese nuclear physicist Ukichiro Nakaya, who could fine-tune temperature, pressure and moisture content in a controlled chamber to grow different snow crystal structures. Bentley's six-sided stars and plates are just a few of the many varieties of structures that exist - prisms, columns, needles, triangular crystals, twelve-branched stars and irregular shapes are just some of the structures that can be grown under specific environmental conditions and are also found all over the world. This probably wouldn't be known if it wasn't for the work of Wilson Bentley.

‘Every crystal was a masterpiece of design and no design was ever repeated’. A photograph of one of Wilson Bentley’s snowflakes. Source: The Guardian

Today in Mill Brook Valley there is a small museum dedicated to Bentley and his work, with walls lined with his photography and his original contraption for taking these photographs. I would love to see this one day. What really captivated me about Bentley and his work was his unrelenting curiosity and his drive to share the beauty of snow crystal structures that would eventually be scientifically translated. This is why, for similar reasons, I like using time-lapse photography to capture the dynamics of glaciers - images are not only scientifically valuable, but also resonate with everyone regardless of their knowledge of snow and ice.

Further reading

This article and this article from the Guardian on Bentley’s photography

The Snow Tourist by Charlie English which contains a detailed chapter on Bentley’s life work and also more generally on studies of snowflakes. I plan on writing a review when I have finished the book - it’s very good so far!