What is going on at Tunabreen?

Tunabreen is a tidewater glacier in Svalbard that has recently been displaying some exciting activity. It is known as a surge-type glacier, with discrete periods where it flows markedly faster and slower. Tunabreen entered a fast-flowing phase in December 2016, which is ongoing at the time of writing. The nature of this fast-flowing phase is atypical for Tunabreen though, throwing into question whether this phase is associated with surge dynamics. What is going on at Tunabreen?!

Tunabreen is an ocean-terminating glacier on the west coast of Svalbard. This glacier is particularly special because of its unique set of dynamics. A large number of the glaciers in Svalbard are known as surge-type glaciers. A surge-type glacier undergoes periods of fast-flow followed by very slow, inactive phases. The nature of this surging pattern is due to the glacier's inefficiency in transferring mass from its upper regions to its terminus (Sevestre and Benn, 2015). It is an internally-driven process. The trigger of this process is unrelated to external influences (i.e. changes in air temperature, ocean temperature, and precipitation).

Tunabreen is one of few glaciers in Svalbard to have been observed to undergo repeated surge cycles. It has surged in 1870, 1930, 1971, and between 2002-2005. We know these surges happened because each surge phase left a pronounced ridge on the seabed which defines the surge extent (Flink et al., 2015). As these surges have been spaced 30-60 years apart, the next surge was not expected for quite a while (at least until 2030).

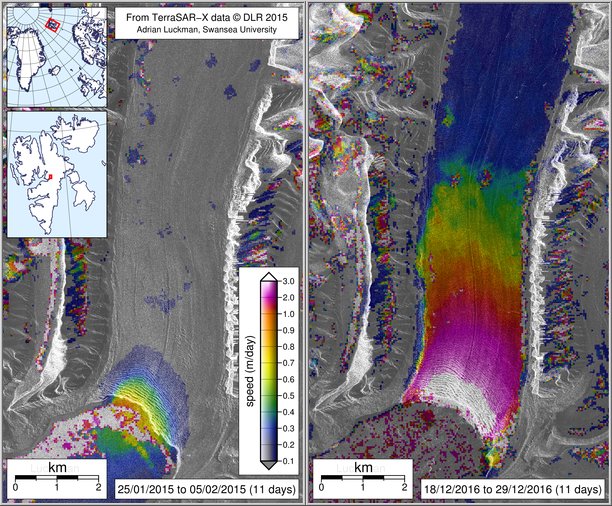

Tunabreen was a very slow-moving glacier between 2005 and 2016, flowing between 0.1-0.4 metres per day (m/day). These velocities were largely derived from sequential satellite imagery. Distinct glacial features were tracked from image to image to determine surface velocities on the glacier. The highest velocities (0.4 m/day) were limited to the terminus area, with very little movement (0.1 m/day) in the upper section of the glacier tongue. It was often difficult to track glacial features from image to image because the glacier was moving so slowly.

A marked speed-up was initially observed at Tunabreen in December 2016. The entire glacier tongue suddenly flowed faster. The terminus flowed >3 m/day and velocities in the upper section increased to 0.3-2.0 m/day. This speed-up continues at the time of writing this blog post (March 2017). It is a dramatic difference from the months and years prior to this event.

The speed-up at Tunabreen shown from feature-tracking through TerraSAR-X satellite images (from Adrian Luckman, Swansea University)

So, is this a surge? is the question on everyone's lips now. In short, we don't know at the moment and this is a difficult question to answer with the short amount of time that we have witnessed these changes at Tunabreen. At the time of writing, there are 4 key observations that need to be considered:

- The timing of this speed-up coincides with record-high temperatures and precipitation for a winter season in Svalbard (as stated in this article by Chris Borstad, a glaciologist at UNIS). This could have had a significant influence on the presence of water at the bed of the glacier, which is understood to lubricate the interface between the ice and the underlying bedrock. This, in turn, promotes sliding and may also cause the glacier to flow faster.

- This winter, sea ice did not form in Tempelfjorden and the fjord area directly adjacent to the glacier front. Sea ice and melange is understood to provide a back-stress against the front of a glacier. This acts as an opposing force to ice flow. Without the presence of sea ice, this opposing force is absent at the front of Tunabreen. Lack of sea ice was also observed in the winter of 2015 (as noted here in a previous blog post).

- The spatial pattern of this speed-up propagated in an upward fashion i.e. an increase in velocity first occurred at the front of the glacier, with subsequent velocity changes progressing up the glacier tongue. The abundance of crevasses on the glacier surface has increased, with the crevasse field extending much further up the glacier tongue than previously. Also, the terminus has advanced roughly 400 m since December 2016, as shown from the sequence of Sentinel images tweeted by Adrian Luckman (and displayed in a post by St. Andrews Glaciology). These observations are indicative of surging dynamics, as stated by Sevestre and Benn (2015).

- This speed-up has occurred 12 years after the previous surge (2002-2005). Surges at Tunabreen have previously been spaced 30-60 years apart from one another. The next surge was not expected until at least 2030. If this speed-up is associated with surge dynamics then it has occurred much earlier than anticipated.

Tempelfjorden in March 2015. Sea ice normally forms in Tempelfjorden up to the ice front over the winter, but it did not form in 2015 and 2016. This also happened in 2006 and 2012. As well as having large implications for the dynamics of Tunabreen, this has also impacted on snow scooter routes across Svalbard. The sea ice in Tempelfjorden has previously been used as a major scooter route for tourist groups and for transporting goods.

These observations can be used as arguments for and against this speed-up being associated with surge dynamics. Whilst the behaviour of the glacier indicates that this may be associated with surge dynamics, there have also been significant changes in external factors which could have played a crucial role in this speed-up. It is important to continue monitoring changes to better understand the processes behind the abnormal behaviour at Tunabreen. It will be interesting to see if this speed-up is sustained through the spring of 2017, and to see how much the terminus will continue to advance into Tempelfjorden. One thing is for certain: all eyes will be on Tunabreen and what it does next!

The front of Tunabreen in March 2017. I was lucky enough to visit Tunabreen earlier this month as part of the Glaciology course that runs at UNIS each year. It was incredible to see this glacier again. We have time-lapse cameras positioned on the mountain ridge (Tunafjell) that is visible in this picture. Hopefully they will give us some insight into the dynamics associated with this speed-up.

Further Reading

St. Andrews Glaciology blog: Unexpected ‘surge’ of a Svalbard tidewater glacier

UNIS post by Chris Borstad on the changes at Tunabreen

Sevestre and Benn (2015) - A comprehensive study on surge-type glaciers and their distribution around the world.

Flink et al. (2015) - Past surge extents at Tunabreen determined by topographic features on the sea bed, derived from multibeam-bathymetric surveying over Tempelfjorden.

Tweets by Adrian Luckman showing the speed-up from TerraSAR-X imagery and Sentinel imagery